Diademed

View All Tags

In Greek culture, the diadem was strongly connected to kingship. Alexander the Great, who spread Greek culture and ideals across a vast empire, was among the first to use the diadem as a deliberate symbol of his claim to universal rule. On coinage minted during and after his reign, portraits of Alexander sometimes featured the diadem alongside other symbols, such as the ram’s horns of the god Ammon, further enhancing his image as both a mortal king and a figure with divine endorsement.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his successors, the Diadochi, adopted the diadem as a key element in their self-representation. These Hellenistic rulers—such as the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in the Near East, and the Antigonids in Macedonia—used diademed portraits on coins to assert their legitimacy as heirs to Alexander’s empire. The diademed head often appeared in a regal, idealized style, underscoring their status as rightful rulers and linking them to the traditions of Greek kingship.

Beyond kingship, the diadem carried connotations of divine favor and protection. In Greek religion and iconography, gods and heroes were often depicted with diadems, signifying their elevated status. By portraying themselves with diadems, rulers positioned themselves as chosen by the gods or even semi-divine themselves, reinforcing their authority both politically and spiritually.

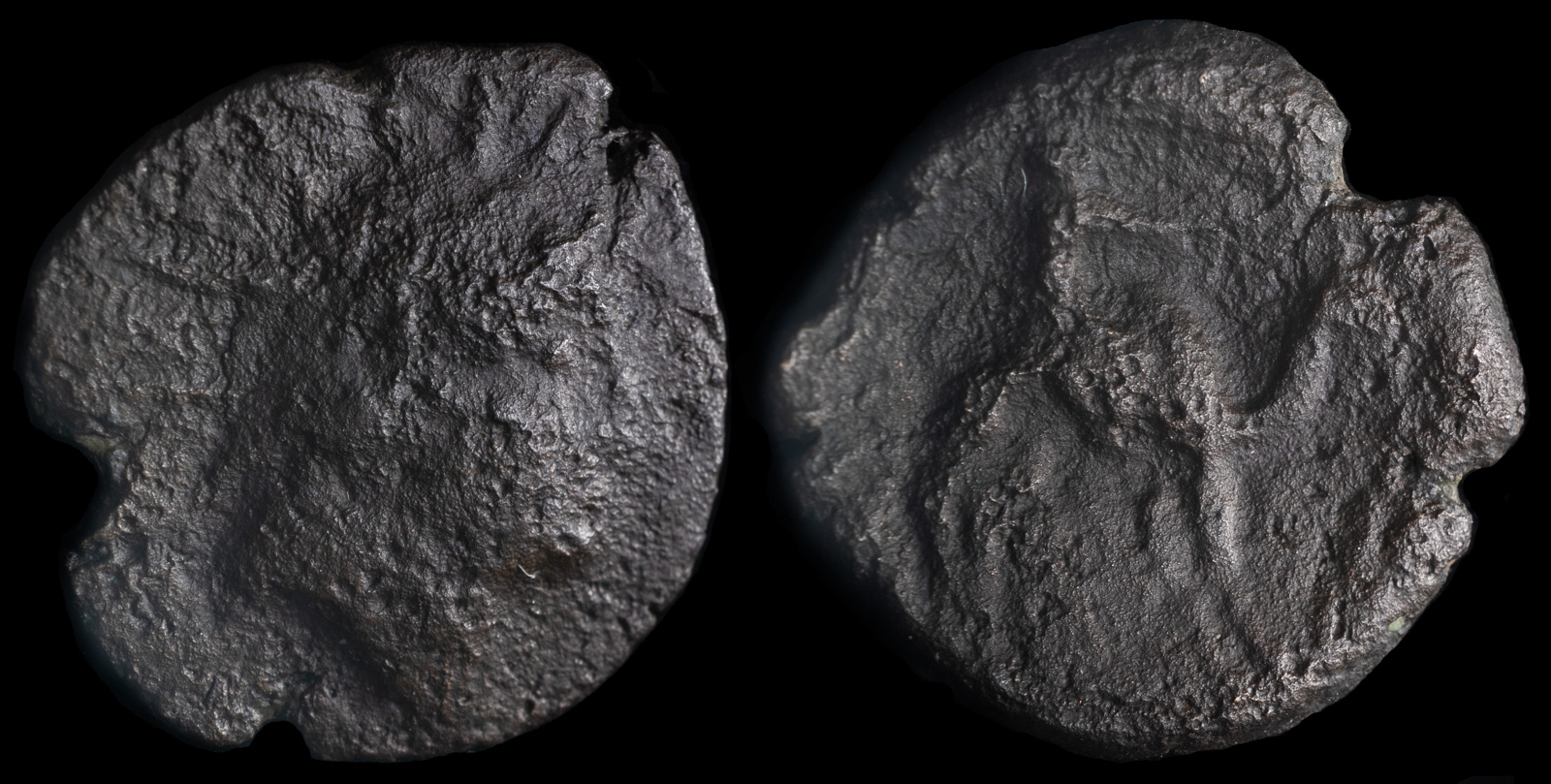

Adiabene, Mesopotamia 125-75 BCE

Aelia Eudoxia 395-401 CE

Amphipolis, Macedon 355-353 BCE

Amphipolis, Macedon ca 187-167 BCE

Apollonia ad Rhyndakum, Mysia 2nd-1st century BCE

Archelaos 36 BCE – 17 CE

Ariarathes IX Eusebes 88/7 BCE

Ariarathes V 134/3 BCE

Ariarathes VII 104/3 BCE

Ariarathes X 42-36 BCE

Ariobarzanes I Philoromaios 83/2 BCE

Ariobarzanes II 63-52 BCE

Ariobarzanes III 52-42 BCE

Aristoboulos w Salome 54-92 CE

Arsames I 240 BCE

Axos, Crete 3rd-2nd cent BCE

Berenikie II 244-221 BCE

Bubon, Lycia 2nd-1st century BCE

Bucephalos 336-323 BCE

Constans 337-350 CE

Constantius II 351-354 CE

Demetrios Poliorketes 306-283 BCE

Diodotos I of Baktria 255-235 BCE

Galeria Valeria 308 CE

Gratian 379 CE

Halos, Thessaly 3rd century BCE

Helena 327-329 CE

Herennia Etruscilla 250 CE

Honorius 393-423 CE

Hyspaosines 124/3 BCE

Jovian 363-364 CE

Juba II w/ Kleopatra Selene 8-15 CE

Koinon of Macedon 218-222 CE

Koinon of Macedon 220-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 222-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 231-235 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 238-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 239-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 239-244 CE

Koinon of Macedon 244-249 CE

Kotiaion, Phrygia 244-249 CE

Kotys IV 171-167 BCE

Laodikeia ad Lycum, Phrygia 133-67 BCE

Lysanias 40-36 BCE

Lysimachos 323-305 BCE

Magnesia ad Sipylum, Lydia 2nd-1st century BCE

Mithradates 180-170 BCE

Mithradates VI 120-63 BCE

Nikomedes I 280-250 BCE

Nikomedes II 110/9 BCE

Nikomedes III 126/5 BCE

Nikomedes IV 92/91 BCE

Orchomenos(?) 336-323 BCE

Perinthos, Thrace 2nd-1s centuries BCE

Phakion, Thessaly 3rd century BCE

Phakion, Thessaly ca 300-200 BCE

Philip II 354-349 BCE

Ptolemy II Philadelphos 256/55 BCE

Ptolemy III Euergetes 246-222 BCE

Ptolemy V 205-180 BCE

Salonina 257-258 CE

Samos, Ionia 310 BCE

Seuthes III, Thrace 324-312 BCE

Severina 275 CE

Stratonikeia, Caria 3rd century BCE

Tarkondimotos 39-31 BCE

Tenedos, Troas 450-387 BCE

Thedosius I 379-383 CE

Tigranes II 80-68 BCE

Vetranio 350 CE